City Brain slashes congestion problems

Hangzhou is one of China’s most important tourist cities. But with a population of seven million people driving nearly three million cars it also had a reputation for being one of the most congested.

But thanks to its City Brain traffic pilot, launched in 2016, it’s already gone from being the fifth most congested city in China, to the 57th.

The City Brain traffic pilot was launched in 2016.

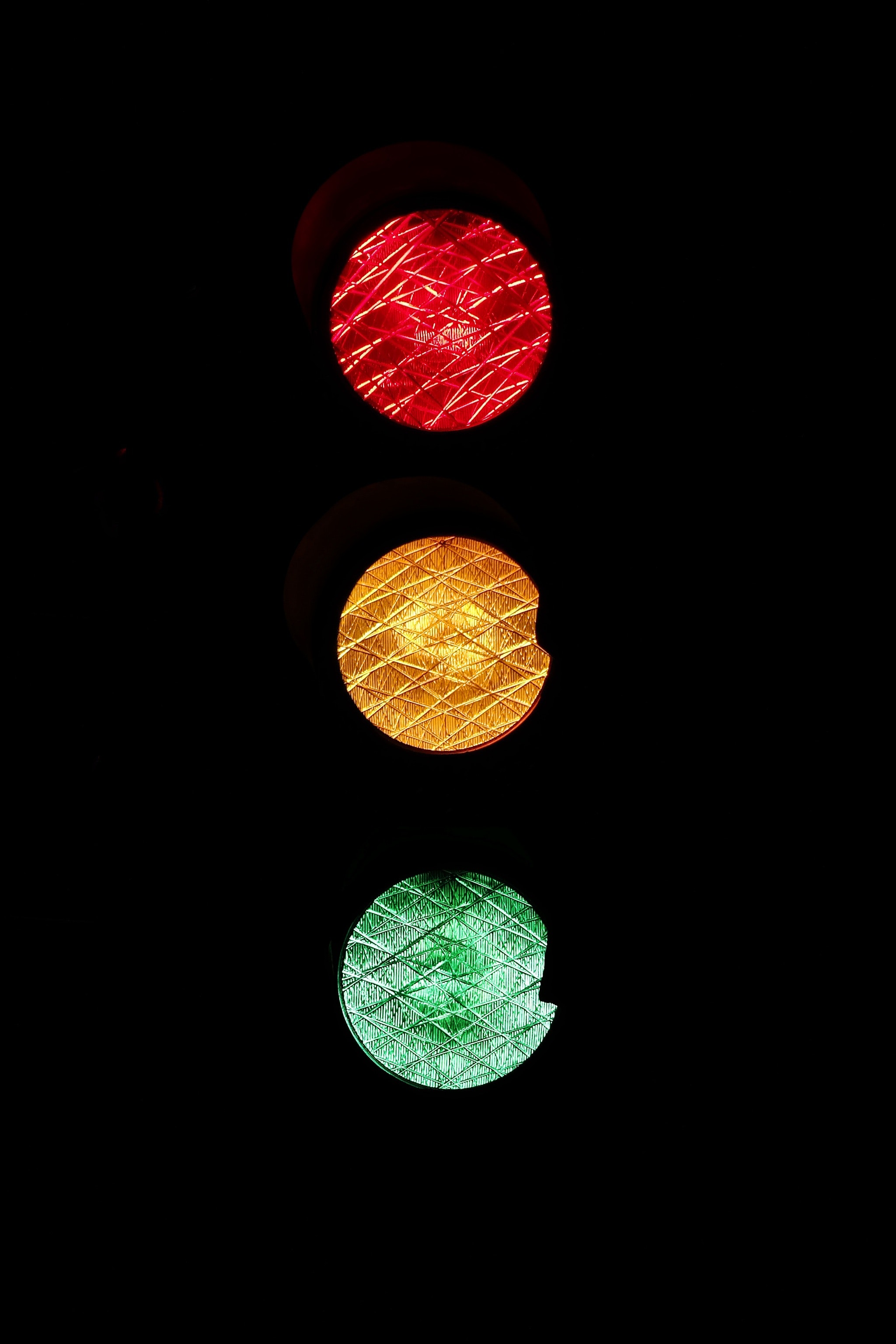

City Brain is the baby of tech giant Alibaba, and uses big data, sensors and artificial intelligence to reduce frustrating bottlenecks. The platform analyses information - including from intersection cameras - in real time, to adjust traffic light sequences at key times in order to account for the higher or lower numbers of cars on the road.

Alibaba says not only has the City Brain shortened commutes, it’s also helped emergency services race to accident or fire scenes in half the amount of time it used to take by controlling traffic lights.

The Hangzhou City Brain traffic pilot is being carried out by Alibaba.

The system is now also being used to warn about infrastructure damage and to predict bad weather.

Dr. Wang Jian, the head of Alibaba’s Technology Steering Committee, who coined the term “City Brain,” said the system is designed to empower a city to act quickly and intuitively. It’s now being used in other Asian cities and could be used to drive development decisions for governing bodies in the future, he predicted.

Version 2 of the system’s just been launched in Hangzhou and will provide specialised data to firefighters, such as water pressure, the number and position of fire hydrants in any given area and the location of gas pipes.

But with any data grabbing come concerns around privacy and surveillance. Social scientist Gemma Galdon Clavell, who’s been working on the ethics of technology, told Wired that the implications are huge.

Photo by Markus Spiske temporausch.com from Pexels

“What is sold as public or safety initiative ends up using public infrastructure and the public to mine data for private uses,” she told Wired. “We’d need to see contracts to assess this, but in my experience cities just give away everything to private contractors and don’t protect data or public return in contracts.”

She also argues this kind of project has the potential for huge data breaches.

“We have seen viruses like WannaCry affecting human lives, like hospitals shutting down after a massive breach.”

But Alibaba says in China people are less concerned with privacy, which allows them to develop the technology faster.