Our changing wai: 20-year freshwater trends to guide local efforts

Supplied article from Land, Air, Water Aotearoa

On 24 September the Land, Air, Water Aotearoa (LAWA) project published updated water quality results for around 3,500 rivers, lakes, estuaries, and groundwater sites. Project scientists say the data are gold for the thousands of people working on freshwater improvement across the country.

A graphic example of a river journey towards restored ecosystem health. At left is a river under pressure with degraded ecosystem health, at centre actions are underway to restore the river, and at right a thriving river ecosystem in the future. (Source: LAWA).

For the first time, New Zealanders can see how their waterways have changed locally over a 20-year period where long-term monitoring data exists. Remarkably, around 1,200 sites have 20-year trends, meaning regional and unitary council scientists have been reliably sampling the water at these places since at least 2004.

Dr Amanda Valois, LAWA River Health Science Lead and Freshwater Team Leader at Greater Wellington, said it’s awesome communities can now see two decades of change on LAWA.

“Today is World Rivers Day and in Aotearoa we’re marking the occasion by making 20-year freshwater quality trends publicly available through the LAWA website.

“As a regional council freshwater scientist, I know how much our waterways matter to people and to the environment and economy.

“The data released by LAWA show many water bodies are under pressure. We’re seeing impaired ecological health at two-thirds of monitored sites across New Zealand, along with declines over time in pollution-sensitive aquatic species,” said Dr Valois.

Dr Valois explained that over the past two decades, both regional and unitary council monitoring programmes have matured and public concern and knowledge about water quality has grown.

“New Zealand has shifted from focusing on point-source discharges to also confronting diffuse pollution coming off the wider landscape, particularly intensive land use. This shift could help explain the mixed water quality trends across the country.

“Land-based solutions like improved farm and urban planning, nutrient management, and riparian fencing and planting are now front and centre,” said Dr Valois.

Today’s National Picture Summaries from LAWA take a nationwide snapshot of freshwater health, while detailed local information is available on the thousands of individual site pages.

Cawthron Institute Freshwater Ecosystems Manager and scientist with the LAWA project, Dr Roger Young said the findings present themes for New Zealanders to be aware of.

“Nutrient pollution is a cross-cutting story, for example you see the influence of nitrogen inputs across groundwater, rivers, lakes and estuaries.

“Faecal contamination remains a challenge with E. coli an issue at two-thirds of monitored river sites, and it was detected at around half of monitored groundwater bores over the past five years.

“There are positives evident in the data, for example ammonia and dissolved reactive phosphorus have improved at sites where point-source discharges have been upgraded,” said Dr Young.

While two-thirds of monitored lakes are in poor or very poor condition, and estuaries face pressures from metal contamination, there’s hopeful signs at both individual sites and national scale. For example, lead contamination in estuaries has improved following regulatory change, showing the environment can recover when pollution sources are controlled.

For communities working to improve freshwater health, knowing that change is possible and being able to track local shifts in water quality is important.

LAWA Project Chair Dr Tim Davie said putting 20-year water quality trends in the public domain is a step forward.

“Over the past two decades we’ve seen a step change in freshwater management with the introduction of national frameworks, regulations, and standards to guide local decision-making.

“Alongside greater rigour in national direction and rules, there’s been substantial non-regulatory momentum with central government support and local government, iwi and hapū, industry bodies, catchment care groups, and other NGOs fencing and planting waterbodies, restoring wetlands, and reducing erosion.

“Regional government freshwater science has also improved, and we now bring together a wider range of indicators to better understand how waterways are really doing.

“I’m proud that 20-year trends now sit alongside the 5-, 10- and 15-year periods. LAWA will continue to put environmental data in the hands of New Zealanders so they can take informed action in their catchments,” said Dr Davie.

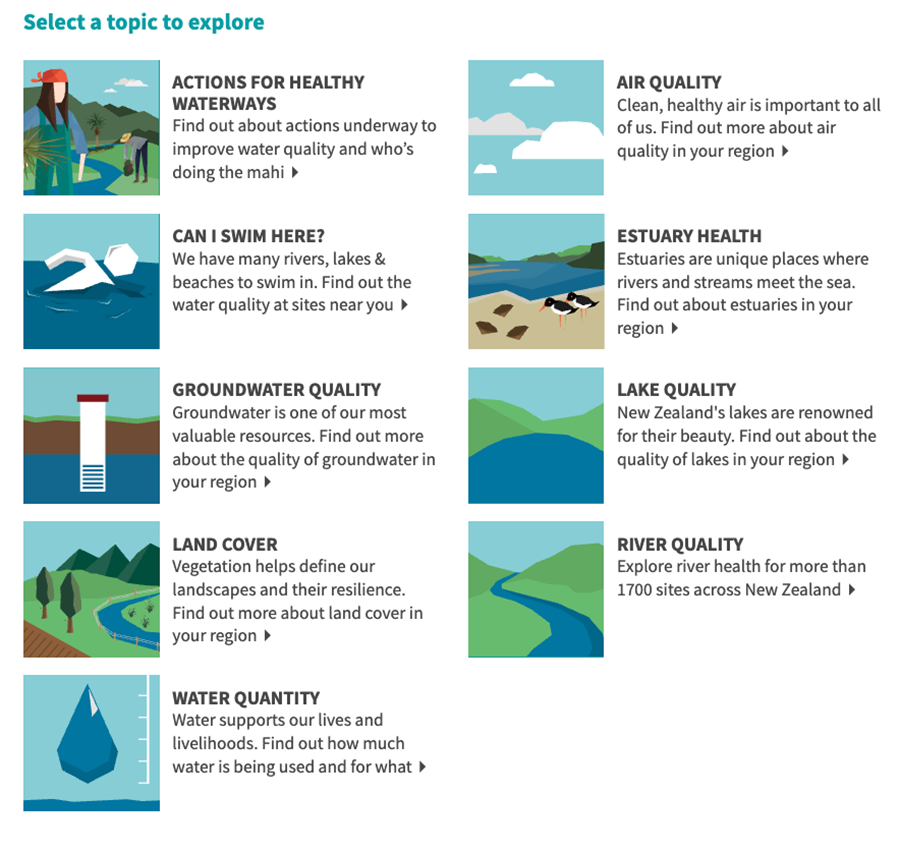

LAWA is designed to help people better understand their environment. Visitors to the LAWA website can explore local rivers, lakes, estuaries or aquifers, and view the state and trends of commonly tracked freshwater health indicators, then put this information into context by considering their local knowledge of land use and activities to take action that supports healthier waters.

Dataset overview

The LAWA River Health National Picture 2025, LAWA Lake Health National Picture 2025, LAWA Groundwater Quality National Picture 2025, and LAWA Estuary Health National Picture 2025 provide national level analyses of comprehensive monitoring data collectively spanning millions of individual data points.

Data are only available for sites where monitoring has been carried out, and monitoring sites are often located in areas at greater risk of degradation from human activities, therefore, this summary provides useful insights yet is not intended to necessarily be a complete and balanced representation of all rivers, lakes, groundwater, and estuaries across New Zealand. Results are most useful at an individual and catchment level.

About LAWA: Initially a collaboration between New Zealand’s 16 regional councils and unitary authorities, LAWA is now a partnership between the Te Uru Kahika - Regional and Unitary Councils Aotearoa, Cawthron Institute, the Ministry for the Environment, the Department of Conservation, Stats NZ and has been supported by the Tindall Foundation and Massey University.